4. Improbableville

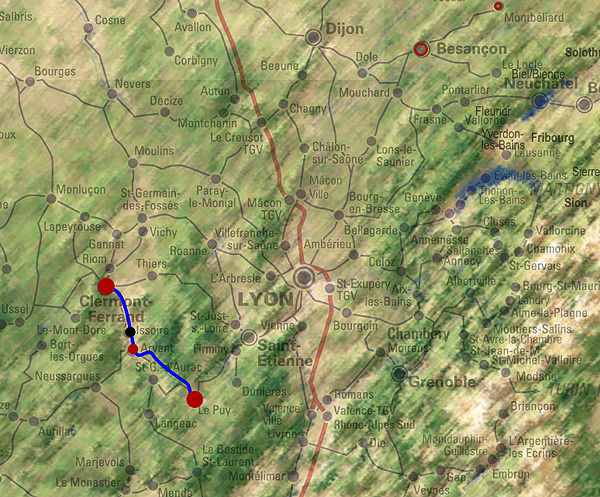

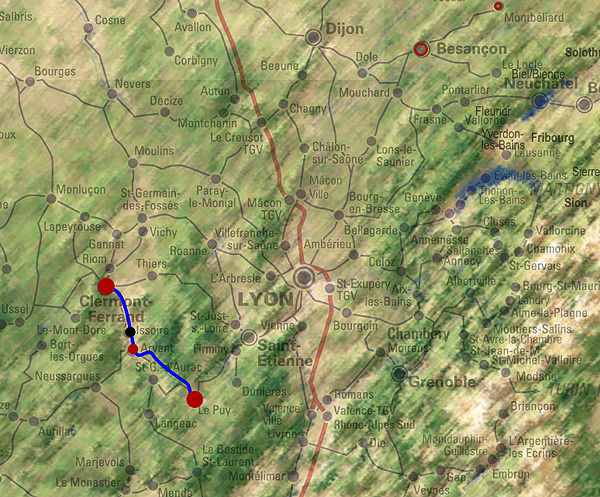

The next morning, I was off to Le Puy (“luh-PWEE,” pop. ~21,000), consulting my Michelin map of France (alas, not a region-specific one) and my copy of the Rough Guide almost compulsively to learn about each new place that the train passed through.

From Clermont-Ferrand to Le Puy there’s actually some very nice scenery…which is good, because there’s not much else there. Geographically it’s pretty wildly up-and-down, nicely forested (but not thickly so), with a sense of being unexplored despite there being a train going through it and little towns here and there along what appeared to be a river valley.

Because this is an area of France at the regional edges of transportation networks whose focus is elsewhere, the trip was done in three stages—two by train, one by bus—and was essentially uneventful. Actually it’s tempting to say it was anti-eventful, especially as regards the tiny town of Arvant where the first leg of the train ended and a 2.5-hour wait for the next train began. Arvant (“ar-VAHN,” regional pop. maybe 4,000), halfway between Clermont-Ferrand and Le Puy, is the smallest town I’ve ever been in, I think, at least in France: this was clear to me within a half a block of the train station, when I realized I could see the other side of town just four blocks ahead. Its breadth, flanking a fairly busy road which evidently linked the little towns of the region, consisted of maybe seven or eight blocks. I saw a pharmacy at one end, a lifeless-looking bar in the middle, and lots of residences—no shops, not even a bakery—and resigned myself to wait it out with supreme calm and patience.

I stood at the far edge of town, beside some fields, just breathing in the rich country air for awhile and looking at the broad, fertile valley and its flanking hills, then returned to the train station (there being little else to do on a sunny day while laden with my bags) by way of a brief conversation with an elderly gentleman whose upper teeth distractingly danced to a different rhythm than his speech pattern. I paced and thought (and watched birds circling and diving high overhead) on the train platform and for the most part got a little more sunburnt.

The connecting train arrived, and we rolled merrily along…for all of six miles, whereupon the train stopped at Brioude (“bree-OOD,” pop. ~7,000) and we all got out to board a bus (covered by my Eurail pass, as it’s an extension of the French rail system) the rest of the way to Le Puy. This large coach was mostly full of mid-teenage French kids, all gabbing but not particularly obnoxiously so, and the driver had the radio on—this being France, the station was playing almost nothing but 1970s American rock and disco. I endured (it wasn’t too bad). When we approached Le Puy the scenery got significantly more interesting than the spotty hills scattered among the plains and the slow elevation increase I’d seen since Arvant, and as we crested one last ridge and descended into the town itself I just looked in astonishment, gave a little laugh, and said “no WAY!”

Le Puy (now officially called “Le Puy-en-Velay” to distinguish it from other Puys…there are a few towns with that name, in part because a “puy” is a regional term for “mountain”) is just goofy, topographically. Its setting is a sort of a bowl, but a bowl with a couple of spikes in it, and most of the biggest spike’s mass is clustered with a nice old city of the classic medieval twisting-streets variety, as well as an abundance of tree cover, as you can see on the cover of the guidebook I bought there. Old and new swirl around each other at street level, at the foot of the rock outcroppings, and so does the traffic, as the “ring road” circles counterclockwise and adds a feeling of constant movement.

My personal narrative about my time in Le Puy is minimal: I got a room at the Étap-Hôtel (as if by way of apology from France for the Aubière saga, this one was across the street from the train station), I wandered and dined, I did some sightseeing. The most eventful of my experiences there involved laundry, and it was no big deal. (Well, I suppose I should note that I didn’t sleep too well the first night thanks to the presence of variously screaming adolescents in a nearby park, which necessitated me regretfully closing the hotel room’s window at what felt like 5h00 but was actually only around 2h30.)

I found Le Puy just lovely, an informal jumble of individually improbable elements all clumped together in a city that’s not exactly touted by French tourism campaigns (at least as far as I’ve seen). One of the city’s historical industries is lacemaking, and that art is represented unoppressively, even gently, here and there, but its biggest long-term tourism draw is its key position as the original starting point for the pilgrimage to the northwestern Spanish city of Compostella (assuming that mid-10th-Century Bishop Godescalc of Le Puy was in fact the first to do it…check out www.saint-jacques.info/anglais/lepuy.htm for an interesting assessment of the story), where what were believed to be the bones of St James were found in the 800s.

Religion—specifically not just Roman Catholicism but that intensified offshoot referred to disparagingly as “Mary worship”—is surprisingly suffusive here. Its acme is to be unmistakably found in the city’s focal point—the huge pale-red statue of Mary holding the baby Jesus, around 66 feet tall from pedestal to crown but much taller-seeming given its position atop the 390-foot-tall Rocher Corneille in the center of town (the statue itself, by the way, was made from 213 Russian cannons captured in December 1855 at Sebastopol by Napoléon III, in the Crimean War; after they were sent to Monsignor de Morlhon, the bishop of Le Puy, it took four months to melt them down and sculpt this statue, “Notre Dame de France”)—but that’s just a gratuitous flourish further up the slope from the Cathèdral Notre-Dame-de-France, which is the city’s true center point (at least in terms of cultural history). Consider how many pilgrims must have passed through that church and its surrounding byzantine-seeming arches in the last ten centuries, and have an unhurried look at the frescoes in the vaults above the top of the steps leading up to the west entrance, and you’ll find yourself swimming in more history than you might have thought you’d see so close at hand. (Then again, if you climbed up the stairs all along the processional route of the avenue de la Cathèdrale and the rue des Tables to get there, a certain practical element of light-headedness may be enhancing the impression.)

The interior of the cathedral definitely carries a feeling of centrality, of being a nexus of energy rather than simply a tourist attraction, but for all that it’s not especially lovely or elegant. It’s heavy, in fact. But it also has the Vierge noire, an 18th Century copy of an ancient dark statue of a seated Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus on her knees (possibly originally of Isis with an infant Osiris, according to MSM’s guidebook Découvrir Le Puy-en-Velay) which was destroyed during the French Revolution; this is costumed and trotted out every 15 August for a procession through town to mark the Feast of the Assumption.

Le Puy’s other obvious physical attraction is the more-ridiculously abrupt Rocher d’Aiguilhe and the little Saint-Michel church at its top. I went there but not to the big Mary statue (the view was impressive even from below the admission gate, and I’d walked plenty by that time and didn’t need to look at a big statue from its feet AND pay for the pleasure) and I’m glad I did: in all photographs (such as on the guidebook cover above, where it’s in the foreground), the slope and stairs and height look daunting to say the least (which helps to discourage out-of-shape tourists from even visiting the gift shop at its base) but in fact it’s not a particularly straining climb, and even if you gave up like a complete wuss somewhere along the way, the view there would be fantastic. From the top it’s truly worthy of the term “breathtaking,” especially if you’re afraid of heights and happen to look over the chest-high wall of the little walkway below the church itself. I’ll let the guidebooks and your own research deal with all of the rich historical detail involved in this place: for me, it was an experience and a treat even though I had to endure Other People while there (these may or may not be tourists but they generally plague my travels by chatting next to the signs which clearly say SILENCE in twenty languages [including theirs] and take flash-assisted photographs of each other beside signs saying NO FLASH in all those languages). The Saint-Michel church is in active use, by the way, it’s not just a remotely perched touristic relic.

Back at ground level, Le Puy offered a delightful array of dining options…by day, anyway. At night the choices were much fewer but still surprisingly diverse. My first night there I happened on La Distillerie (11, rue Porte Aiguière) just as I was giving up hope of finding anything open and occupied (dining alone in an empty restaurant while travelling feels terribly awkward, to me) and bracing myself for a meal based on the contents of the vending machine at the hotel. I had the classic salt-pork dish le petit salé with the famous local green lentils, with some wine, and while it wasn’t a stellar meal I certainly was attentive to the setting: what in the U.S. would seem a “themed” bar/restaurant with jumbled nostalgic trappings everywhere was here almost agreeably accomplished. It had interesting partitioning of dining areas that felt like oddly juxtaposed dining cars, and the clientèle was intriguingly young and electric. That my waiter was a total studmuffin only complicated my impressions.

I was surprised to find such impressive beauty as I did in the stocky church of Saint-Laurent, at Le Puy’s center’s northwest edge, the next morning: there’s some stained glass there that moved me deeply in its color and purity (the west windows, above the narthex, contain a gorgeous shade of deep cornflower blue that I’d never seen before in the luminous medium of stained glass), and the floor has a compelling inlaid pattern of paths. By comparison the Cathédrale, with its Black Madonna and all the pilgrimage history, seems grander but less personally meaningful. There’s no question that the latter is the city’s historic and spiritual lodestone, but the Église Saint-Laurent is a fine, discreet reminder that the cathedral has no monopoly on poignancy and significance.

Luckily for me the church was almost entirely unoccupied while I was there; the only person I recall seeing was a woman who came to clean the altar area and set up flowers and such for the following day’s services. We chatted a bit about Le Puy…when I enthused about how interesting and lovely I found the city, she modestly acknowledged “c’est quelque chose…” (“it’s something, alright…”) with a sidelong smile. She offered to turn on the church’s full lighting for me so I could better see the paintings lurking in its shadowy galleries, but I found the effect of the shadow was to give the place that much more magic: colorful petals of stained-glass light dappled the floor, creating a glow which lit the dark space from below, exquisitely.

On my full day in Le Puy I had my laundry washed—that is, I went to a laundromat fully indending to do it myself, but the woman who ran the place indicated that she’d take care of it, and she did. But I think she was probably beside herself when the two formerly-white shirts in my load came out an odd pale sea-green-ish shade: I’d bought some black pants just before travelling and forgot that I’d need to wash them once or twice before they were safe to wash with anything but darks. Thankfully the color kind of amused me, and I knew it would eventually wash out more, so I reassured her that it was no problem and anyway was entirely my fault.

Meanwhile I’d had a simple jambon/gruyère crêpe (from a little stand along the place du Breuil, which is the city’s main plaza and is flanked by the bigger cafés and civic buildings) for lunch in the Jardin Henri-Vinay, a small-ish park in the city’s south center, got a copy of Le Monde and read for a bit, watched a game of boules being played by an amusingly vocal bunch of older locals on the park’s west edge, and walked around the south part of town’s slopes. I’d also very casually browsed around the marvelous open-air Saturday market (stretching from the Place du Plot to the Place du Martouret, I believe), which had everything from cheeses to live rabbits and all kinds of tempting produce and meats making me wish I had access to a kitchen and were staying for a week. (This was also the day I climbed to the Saint-Michel church atop the Rocher d’Aiguilhe. Those were some sore feet by the end of this day, especially considering how much walking I’d been doing since the trip began.)

I didn’t notice this at the time, but Le Puy was so interesting even as I was just strolling around that I only momentarily thought to look for an Internet café where I could catch up on news and email. I was more interested in finding a FedEx place where I could ship home some of the clothes I’d brought with me—dressy stuff, which can be very useful when travelling but can amount to dead weight (in the form of the shoes especially) if they’re never used, and by this point I was foreseeing a low-key journey.

My one regret about my visit was that I couldn’t buy a bottle of the locally produced liqueur verveine (it is presumably similar to chartreuse, as it too is made from a concoction of herbs—only 30 as opposed to chartreuse’s 130—and its name obviously refers to the herb verbena): I’d have to lug it all over the place with me for the next two weeks, so it seemed more sensible to wait until I got back to the U.S. and get some there…only upon returning to Seattle I discovered that verveine isn’t readily available outside of France (and possibly not even outside of the Le Puy area).

Dinner the second night (after a lovely pause at my hotel, where a light breeze blew cherry-blossom petals into my room as a gentle-but-welcome rain cooled the scene) was a very nice canard au cidre (duck cooked in a cider broth) at Le Marco Polo, a seemingly small restaurant a ways up the town’s main hill. I say “seemingly” because what appeared to be the only room was in fact only the front dining area; another is just out of sight behind it, so they were able to accommodate the many people who came in that night. The atmosphere was almost dressy but wonderfully convivial, and now and then people would arrive who knew others dining there and group conversations would ensue beyond the table area. I had a nice demi of a Saint-Nicolas de Bourgeuil (domaine Oliver 2004) with dinner; as I was awaiting it, I was surprised when the waitress walked out of the restaurant, crossed the tiny street, and just opened the door of the discreet shop across the street and walked into what was apparently the restaurant’s wine cellar. How cool! Dinner was so nice (note that I used this adjective twice already in this paragraph) that I bent my usual no-desserts standard approach to ending a meal and had a lemon sorbet to seal the impressions.

I slept contentedly and comfortably at the hotel and left VERY early the next morning to get a jump on Switzerland, with Le Puy definitely bookmarked in my mind for exploration down the road.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

Text © 2006 Mark Ellis Walker, except as noted